Old MacDonald Had a Farm...

When a family farmer hands down their land, are they passing on a business? Their family heritage? A way of life? Or even a piece of national security?

Labour's latest budget has sparked a fierce debate by introducing a cap on farmers' inheritance tax exemptions – a policy that has, until now, let a farm’s assets pass freely between generations for decades.

For supporters of the new change, it's an overdue end to an unfair tax loophole at a time when the country’s debts are exploding; for the farmers and those who support them, it's a threat to the very foundation of British farming.

Context

Before we dive in, a few housekeeping items: I am neither a farmer nor a tax expert. My closest connection to agriculture is successfully keeping a basil plant alive for just shy of three whole weeks, and my expertise in taxation extends to just about managing my own self-assessment returns (with only minimal sobbing).

What I am, however, is deadly allergic to oversimplified arguments and childish bickering by people who haven’t even done the bare minimum of research. As an interested citizen, I want to make sure my own opinion is based on more than the charismatic words of a YouTube influencer and so, over the last few days, I've spent a bit of time reading government papers, tax legislation, farming forums, media, and economic analyses. Yes, I know what you’re thinking … I am really fun at parties.

While this article won't tell you who's right or wrong, I hope it can help you (and me) to:

Understand why everyone is kicking off.

Get up to speed with what the data currently suggests.

Scrutinise the claims of others with more confidence.

A final note: all data and figures cited here come from publicly available sources, which I've referenced at the end. If you spot any errors, please let me know. I'm always happy to be corrected, especially by people who really know what they're talking about.

The Basics

How did it used to work?

Prior to 1976, farming families often faced a stark choice upon inheritance: sell part of the farm to pay death duties, or lose it entirely. This was particularly painful during a period when farming was rapidly modernising and needed stability, not fragmentation.

Since 1976, the approach to taxation has changed a number of times - I’ve tried to capture the salient points here but please do keep in mind it’s a high-level picture.

Note: If you’re not really interested in the history, you can skip straight to the “What about now?” section.

1976:

Agricultural Property Relief (APR) introduced at 50%

First recognition that farms needed special protection from inheritance tax

Only applied to land actively used for farming

1981

Business Property Relief (BPR) introduced.

Not farm-specific but created new opportunities.

Meant business assets (like farm equipment) were eligible for relief.

Created the foundation for a future "double relief" strategy (i.e. APR + BPR)

1992

Game-changing reform: both APR and BPR reliefs increased to 100%

This created the powerful "double relief" situation where farmers could protect:

Agricultural value through APR

"Hope value" (development potential) and business assets through BPR

How did it work for everyone else?

Inheritance tax for most other folks (without a business or farm to pass on) has been reasonably consistent since about 1986; basically there is a tax-free threshold and above that, you pay 40% inheritance tax.

It’s also possible to “gift” assets to your children. Gifts made 7+ years before death are exempt from IHT and there is sliding scale of tax relief if you don’t make it the full 7 years. [Note to self: re-order fish oils and multi-vitamins]

It’s important to note too that farming families are also eligible for these tax-free thresholds and benefits i.e. it’s possible to take advantage of both the tax-free allowance that regular folks use and the other schemes such as APR/BPR.

What about now?

Well, for most folks, as I said, it’s not really changing much:

Tax free allowance for Nil-Rate Bands (up to £500,000)

Basic Nil-Rate Band = £325,000

Residence Nil-Rate Band = £175,000

Pay 40% on anything above their Nil-Rate Bands

No special payment terms (tax due within 6 months of death)

Need to sell assets if cash isn't available to pay

For farming families, it’s changing to:

Only first £1M of agricultural/business property still completely tax-free.

Multiple family members can each use the £1M threshold (so husband and wife could protect £2M)

Pay 20% tax (vs everyone else's 40%) on farming assets above £1M

Can still use the tax free allowance for Nil-Rate Bands (up to £500,000)

Get 10 years to pay the bill, interest-free

Examples

Before we get to the “Is this fair?” part, it’s worth going through a few examples for a typical scenario - married couples passing to their children. Obviously, there are many possible configurations here but I think this one illustrates the differences well.

If you don’t care about all the details, skip to the “Inheritance Tax Due” table at the end.

Boundary Case - £3m estates

Example A1: £3m farm estate ~ Pre-2024 (unlimited relief)

All agricultural property 100% exempt (unlimited)

Plus £650,000 tax-free (Combined Nil-Rate Bands: 2 × £325,000)

Plus £350,000 tax-free (Combined Residence Nil-Rate Bands: 2 × £175,000)

Total Tax Bill: £0

Example A2: £3m farm estate ~ Post-2024 (capped relief)

First £650,000 tax-free (Combined Nil-Rate Bands: 2 × £325,000)

Plus £350,000 tax-free (Combined Residence Nil-Rate Bands: 2 × £175,000)

Plus £2M tax-free (Combined Agricultural Property Relief: 2 × £1M)

Total Tax Bill: £0

Example A3: £3m estate (no difference before or after 2024)

First £650,000 tax-free (Combined Nil-Rate Bands: 2 × £325,000)

Plus £350,000 tax-free (Combined Residence Nil-Rate Bands: 2 × £175,000)

Remaining £2M taxed at 40%

Total Tax Bill: £800,000 (due within 6 months)

So, for a £3 million estate, the farming family pays no inheritance tax whilst the non-farm family must pay £800,000.

Note here that there was no difference for the farming family pre/post 2024 as the estate didn’t exceed the new APR threshold. Lets look at a bigger example.

Bigger Case - £5m estates

Example B1: £5m farm estate ~ Pre-2024 (unlimited relief)

All agricultural property 100% exempt (unlimited)

Plus £650,000 tax-free (Combined Nil-Rate Bands: 2 × £325,000)

Plus £350,000 tax-free (Combined Residence Nil-Rate Bands: 2 × £175,000)

Total Tax Bill: £0

Example B2: £5m farm estate ~ Post-2024 (capped relief)

First £650,000 tax-free (Combined Nil-Rate Bands: 2 × £325,000)

Plus £350,000 tax-free (Combined Residence Nil-Rate Bands: 2 × £175,000)

Plus £2M tax-free (Combined Agricultural Property Relief: 2 × £1M)

Remaining £2M taxed at 20%

Total Tax Bill: £400,000 (payable over 10 years interest-free)

Example B3: £5m estate ~ (no difference before or after 2024)

First £650,000 tax-free (Combined Nil-Rate Bands: 2 × £325,000)

Plus £350,000 tax-free (Combined Residence Nil-Rate Bands: 2 × £175,000)

Remaining £4M taxed at 40%

Total Tax Bill: £1.6M (due within 6 months)

So, for a £5 million estate, the farming family paid no inheritance tax before 2024 and will now have to pay £400,000 over ten years. The non-farm family must pay £1,600,000 within six months, usually by selling assets.

Okay, okay, I know what you’re thinking…

“Three million quid! That’s a nice problem to have. I’ll be lucky if I finish my days with a full tank of petrol and a Sky+ subscription!”

Yes, whilst it’s true that for most people, the tax free thresholds are pretty generous, these estate sizes are not particularly big by farming standards - and so, whilst at first it seems hard to feel sorry for anyone with millions of pounds of assets, keep an open mind for now - we really need to look at the farmer’s side of the story first.

Warning: Though we’re done with the tax calculations for now, there is plenty more detail coming up. If you’ve gotten this far, I’d suggest you make yourself a hot drink and stretch your legs before we jump down the next rabbit hole.

Why are farmers unhappy? Seems like a good deal to me.

In this section we’re going to discuss the farmer’s point of view on why limiting this tax relief is a bad idea. But, before we do that, let’s quickly hop in the time machine and take a look at why this relief was introduced in the first place…

Original Justification for Agricultural Property Relief (APR)

As I mentioned earlier, Agricultural Property Relief (APR) was introduced as part of the 1976 Finance Act for the following reasons:

To protect working farms from being broken up to pay inheritance tax (then called Capital Transfer Tax).

To help maintain the continuity of British farming by enabling farms to be passed down through generations.

To prevent farmers from having to sell land to pay tax bills, which could make farms unviable.

The initial rate was 50% relief on the agricultural value of qualifying assets; this was subsequently increased to 100% in 1992 during John Major's government. The reasons cited for the increase were largely a stronger expression of the original position:

Recognition that even with 50% relief, many farms were still struggling with inheritance tax burdens.

A desire to further protect family farming traditions and maintain agricultural land in productive use.

Concerns about the viability of British farming during a period with many economic challenges.

Alignment with broader Conservative government policies supporting rural communities and agriculture

Further Justification

A lot changes in thirty years (especially my lower back pain) and so you’re probably wondering whether the original reasons for introducing APR are still valid. Well, if you talk to the farmers, there are more reasons now than ever - let’s take a look at some of the key points:

Food Security - Sovereign food production is fundamental to national resilience, with UK self-sufficiency declining rapidly in the last several decades.

Asset-Rich, Cash-Poor Reality - Farm values may look impressive on paper, but they generate a surprisingly small amount of cashflow.

Supermarket Squeeze - Pricing pressures from major retailers severely constrain farm income

Preservation of Family Farms - Forcing sales to pay tax could end generations of agricultural expertise and heritage

Environmental Stewardship - Family farms often maintain crucial biodiversity and environmental benefits that larger corporate farms might not prioritise.

Cumulative Impact - This isn't happening in isolation; it's the latest in a series of financial pressures on farming

Food Security: A Growing Concern?

The UK's food self-sufficiency has dropped to 59% from 78% in the 1980s1, marking a potentially concerning trend in national food security.

Recent global events have highlighted this vulnerability:

Brexit disrupted established supply chains.

Ukraine conflict drove up grain prices by 28% in 20222

COVID-19 exposed fragility of just-in-time food delivery systems

Climate change threatens traditional growing patterns

Every family farm lost potentially reduces our food sovereignty further. While large agribusinesses might fill some gaps, they typically focus on monoculture crops rather than diverse food production that characterises family farms.

Asset-Rich, Cash-Poor Reality: Beyond Paper Values

The concept of being "asset-rich but cash-poor" is thrown around so often it risks becoming meaningless, but in farming it's a stark reality that shapes everything from daily operations to generational planning.

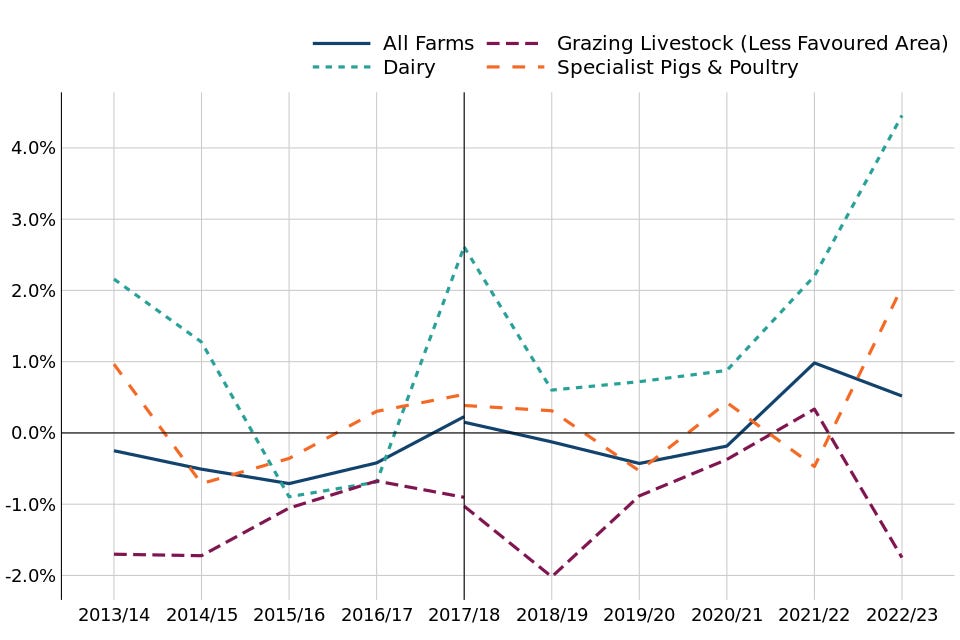

To understand why, we need to look at the unusual business model that underpins modern farming: it requires enormous capital investment in land and equipment to generate what are, by most business standards, very modest returns of 0.5-1% on capital.3

Sticking with our £5M estate example from earlier, let’s break it down a little further.

Land: 350 acres at ~£10,000/acre = £3.5M

Farm buildings and house: £800,000

Equipment (tractors, harvesters, implements): £700,000

Annual maintenance costs: £15,000-£20,000

Annual profit: £25,000-£50,000 (0.5-1% return on capital)

This creates a situation where farms appear wealthy enough to generate massive tax bills but lack the liquid assets to pay them. A farmer might be technically worth millions on paper while taking home less than a junior office worker in London.

Even with the 10-year, interest-free payment term, many farms would need to sell land - their income-generating asset - to pay the tax on it, creating a downward spiral where reduced acreage leads to reduced income, making future payments even harder to meet.

Supermarket Squeeze: A Matter of Margins

Warning: A quick word about agricultural data: trying to get clear figures from farming is rather like trying to milk a cow in the dark - you know roughly where everything is, but precision is a bit optimistic.

The figures here come from DEFRA, the ADHB, and the ONS, and while they're my best attempt to capture recent trends, they should be treated as indicative rather than absolute.

Let’s take a look at how things have changed for both farmers and retailers since 2019.

As you look at this table, it might suggest a simple narrative of supermarket profiteering in dairy and pork, while grain farmers appear to be the winners (I’ve double checked the wheat data, as I found this surprising - it does seems correct. That being said, I think this may be due to some lingering effects of the Ukraine war and associated surges in wheat prices.)

Now, what we’re not capturing here is the input costs associated with producing those products. The most recent data from AHDB4 shows how these input costs have also affected each product.

Looking at this table, we can see that, with the exception of Grain (which I believe could be an artefact of the Ukraine War) farmers costs are going up quicker than their sale prices.

As I looked through the raw data, one thing that struck me, as a non-farmer, is just how variable these prices are on a week-to-week basis. I think that’s often missed out of the pro-cap argument and does provide a fairly strong justification that farmers are, at times, operating extremely close to the wire.

For further information on this topic, I’d encourage you to read the Sustain report which goes into more detail on the percentage of each product’s sale value that actually reaches farmers - the numbers are quite eye-opening.

Breaking the Chain: The Risk to Family Farming

The inheritance tax debate isn't just about balance sheets and tax rates - it's about preserving something more fundamental.

Multi-generational farms carry with them decades, sometimes centuries, of accumulated knowledge about their land. From understanding the quirks of local drainage patterns, to knowing which fields flood first in wet winters, to recognising subtle soil variations across their acres - this is expertise that can't necessarily be downloaded from a manual or learned in an agricultural college.

When farms are forced to sell or break up, we don't just lose agricultural businesses; we lose living libraries of local agricultural knowledge.

Death by a Thousand Cuts: The Cumulative Burden

If inheritance tax existed in isolation, it might be a different story. But for UK farmers, it's the latest addition to what feels like an agricultural version of Jenga - pull out one more piece and the whole thing might come tumbling down.

Recent years have delivered a perfect storm of challenges: Brexit reorganised subsidy systems almost overnight, Net Zero requirements demand expensive equipment upgrades, energy costs have skyrocketed, and extreme weather events are becoming distressingly routine. Each of these might be manageable alone; together, they're testing even the most resilient farms.

Whilst, I don’t have time to deep-dive into all this, I do think there are a multitude of headwinds facing farmers. In fairness, the UK budget acknowledged this in the latest budget and so we’ll have to wait and see whether this turns out to be sufficient -

At the Budget, the Chancellor also announced £5 billion to help farmers produce food over the next 2 years – this is the largest amount ever allocated for sustainable food production.

This is alongside £60 million for the Farming Recovery Fund which will help farmers recover from the impact of flooding. We are also investing £208 million in protecting the nation from outbreaks of serious diseases that threaten our farming industry, food security and human health.

The Hidden Costs: Environmental and Human Impact

Farming isn't just about production figures and profit margins. Family farms have traditionally been the custodians of our countryside, maintaining the patchwork of hedgerows, woodland corridors, and natural habitats that industrial-scale farming often struggles (or doesn’t care) to preserve.

The human cost is equally concerning. Farming has a higher suicide rate than many other occupations, and, whilst the reasons for this are complex, financial pressure is often cited as a major factor.5

So, when people talk about "preserving farming heritage," they're not just being sentimental - they're talking about maintaining a delicate balance between food production, environmental stewardship, and human wellbeing.

International Context: What are other countries doing?

Agricultural IHT relief varies significantly across developed nations. For example, France provides a 75% reduction, Germany maintains substantial relief for family farms, and Ireland preserves a 90% agricultural relief rate. The United States also offers specific estate tax exemptions for farming businesses, though the implementation differs from European approaches.

This international variation in tax treatment reflects different national priorities around food security, rural economies, and agricultural sustainability. While most developed nations maintain some form of agricultural relief, the specific mechanisms and levels of support vary based on local economic conditions, farming structures, and political priorities.

As we examine the counter-arguments to agricultural relief, these international examples provide useful context - not necessarily as models to follow, but as reference points for understanding different approaches to balancing tax revenue with agricultural sustainability.

Counter Arguments

In this final section (yes, you’re nearly there!), I want to provide the counter-points and counter arguments for the those in favour of this change.

Generally speaking (once you filter out the socialist trolls on social media) the argument stems from a feeling of unfairness and a justified push back against rich landowners who are exploiting this policy to pay much less inheritance tax than the rest of the population.

The Question of Fairness and System Exploitation

Fundamental Equity Issues

The debate over Agricultural Property Relief (APR) centres on a fundamental question of tax equity. While the agricultural sector certainly faces unique challenges, the unlimited nature of the previous relief system has raised legitimate concerns about whether it represents a fair distribution of the tax burden across society.

Like we saw in the earlier examples, a professional with an estate valued at £3M, accumulated through decades of earning and prudent investment, faces a 40% inheritance tax bill on the portion above the nil-rate band. In contrast, an agricultural estate of equivalent value could potentially pass to the next generation entirely tax-free.

This disparity becomes particularly striking when we consider other essential professions - doctors, nurses, teachers, small business owners - who face standard inheritance tax rates despite their crucial societal contributions.

Supporters of the change would say that, it’s not so much about taking more from farmers as it is about not passing the buck onto the rest of the public. At a time when it’s not unheard of to see nurses collecting food from food-banks, it’s completely justifiable to scrutinise any part of UK tax policy that offers, essentially unlimited tax breaks to some portion of society.

System Exploitation and Unintended Benefits

The unlimited relief system has, perhaps inevitably, attracted attention from wealthy individuals and corporations seeking to minimise their tax exposure. Rather like finding a perfectly legal but somewhat questionable loophole in the cricket rulebook, certain entities have developed sophisticated strategies to maximise their agricultural holdings primarily for tax purposes.

Patterns of Non-Agricultural Investment

Analysis of land registry data reveals several concerning trends:

Large-scale acquisition of agricultural land by investment funds

Significant increases in farmland purchases by high-net-worth individuals with no prior farming experience

Corporate restructuring of existing agricultural holdings to maximise tax efficiency

These patterns suggest that a system designed to protect family farms is increasingly benefiting entities far removed from traditional agricultural operations. Recent investigations by tax authorities have identified numerous cases where:

Minimal agricultural activity occurs on land classified for relief purposes

Holdings are structured to maximise tax advantages while minimising actual farming operations

Land is held primarily for capital appreciation rather than agricultural production

And, I’m not going to name names here but, some of these farms are incredibly well vacuumed 😉.

Scale of the Issue

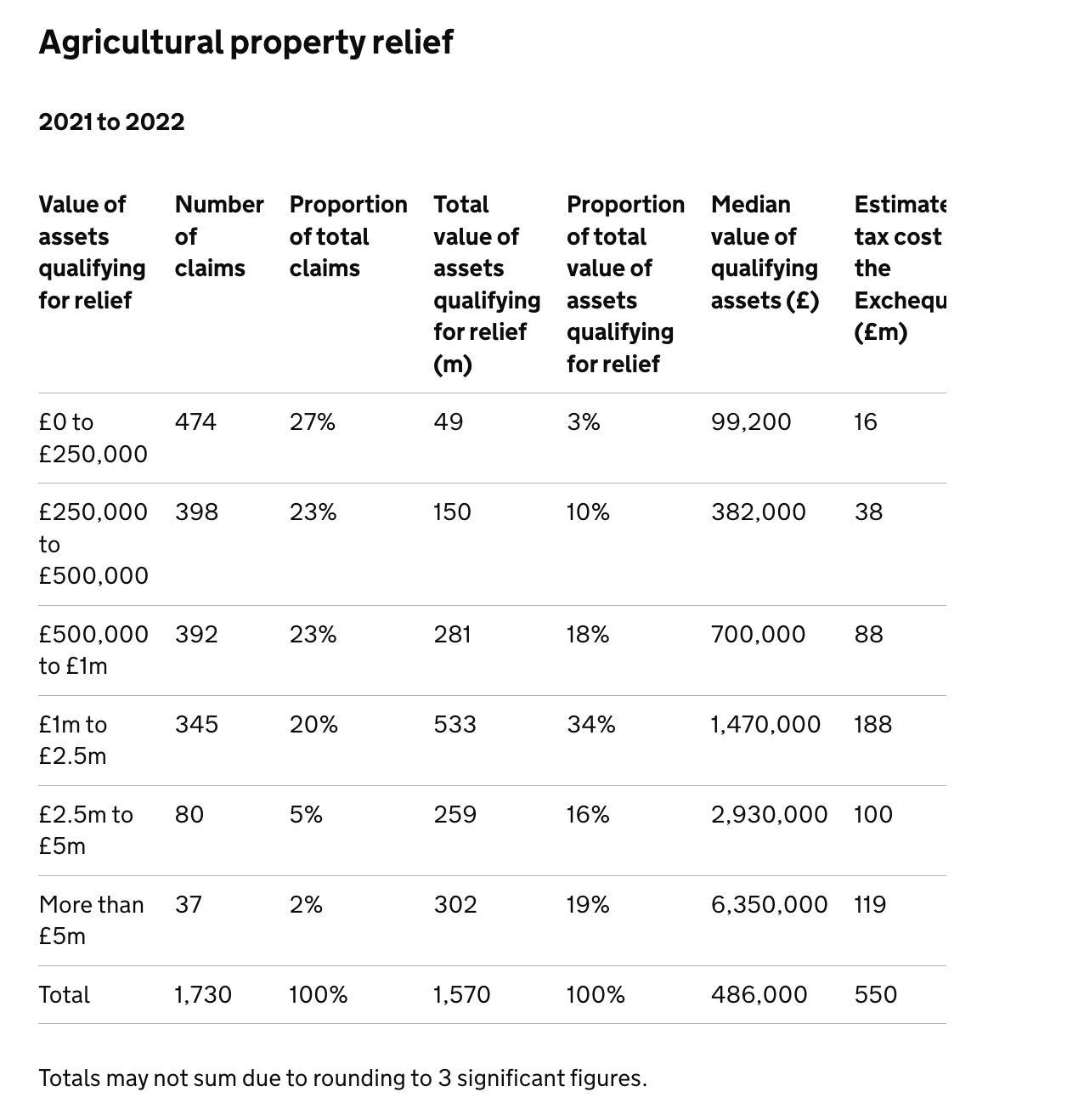

The proportion of the relief being handed to the biggest farms is substantial. In fact, this is outlined in reasonable detail on the Governments own explainer site (below)

The government is better targeting these reliefs to make them fairer, protecting small family farms.

The latest figures show that the top 7% (the largest 117 claims) account for 40% of the total value of agricultural property relief. This costs the taxpayer £219 million. The top 2% of claims (37 claims) account for 22% of agricultural property relief, costing £119 million.

It is not fair for a very small number of claimants each year to claim such a significant amount of relief, when this money could better be used to fund our public services.

It’s worth saying at this point that there is major disagreement on the government’s evaluation of how many farms will be affected by this change (and to what degree) but, even allowing for a large margin of error, the distribution of relief doesn’t line up well with the “Labour are attacking small farmers” argument.

On the other hand, £219 million is not an enormous number in the grand scheme of things. That’s not to say we should let “perfection be the enemy of better” but, given the government’s commitment to this policy in the face of major push back from the public, it seems like this could be more of a statement of principles than a surgical fiscal tactic.

The Case for Reform

The introduction of a cap represents an attempt to rebalance these inequities while maintaining protection for genuine family farming operations. Though, I’m generally in favour of lower taxes, if we have to have them, then they should be fair. I really can’t argue with that.

Now, what we can argue about is whether using a strict threshold value is appropriate and, even if it is, whether this threshold value has been selected intelligently. To do that, we really need to zoom in on perhaps the most controversial part of this discussion…

How many farms are going to be affected?

By any measure, this seems to be the most hotly contested data point. It came up time and time again during my voyage across the swamps of social and mainstream media.

Frankly, anything I say here should be regurgitated with extreme caution; it’s a fast moving debate and there is so much tribal yelling that it’s hard to cut through to the facts but…I’ll try.

Firstly, this is what the Government said…

The reforms will apply from 6 April 2026. Most estates will not be affected by the changes.

Reforms to agricultural property relief are expected to affect the wealthiest 500 estates each year with smaller farms not affected by the changes. So that means almost three-quarters of estates claiming agricultural property relief would not be affected by the changes, based on the latest available data.

This statement was met with extreme skepticism from farmers and their union representatives who simply do not believe that so few farms can be valued below these thresholds.

On the other side, a number of tax experts independently validated the claims made by the Government and broadly agreed.

From my (laypersons) perspective, I think the problem here is that many commentators (on both sides) seem to lack an understanding of the nuance and detail required to evaluate the claims being made. (Shocking, I know)

On the one hand, we have farmers trying to parse tax legalese so that they can work out how it applies their situation and, on the other hand, we have tax experts who are having to rapidly get up to speed on how farming works in the real world.

So, how can we work this out?

Well, on top of the Government’s claims, an obvious place to start is to look at the claims for APR relief that have actually been made i.e. what did claimants report their agricultural property was worth when they claimed this relief in the past. I haven’t found last year’s data but the data for 2021-2022 should at least be indicative and can be found here.

So, based on this data, you can see why “500 farms” has been used as a guide for the number of farms affected - there are only 462 farms that claimed APR relief on assets worth more than £1M.

If you then factor in that married couples can both claim the relief and apply their own Nil-Rate and Residence Nil-Rate allowances - this number could be as small as 100 farms per year.6

Valuation Confusion

Another problem here is that, farmers are saying, quite validly, that these farm valuations seem really low and that it can’t possibly be right that there are all these farms with such low valuations well … yes and no.

The value of the assets used for APR is not the marketable value of the assets - it’s the agricultural value. So, if a farmer has had an estate valuation at say £5m - that is likely to be much higher than the agricultural value of the land (since it could be used for more profitable purposes like home building etc).7

For the purposes of this Chapter the agricultural value of any agricultural property shall be taken to be the value which would be the value of the property if the property were subject to a perpetual covenant prohibiting its use otherwise than as agricultural property

So basically, the threshold values in the APR stats can’t be used in conjunction with numbers from an estate valuation unless they’re specifically evaluating the agricultural property value.

So … the Government is right then?

Well, I’m really not sure. This is where it gets a bit more complicated and where the pointy end of the argument is at the moment.

Remember when we talking about the history of APR and there was the mention of “double relief”? That’s very relevant here as I don’t think the APR data should be viewed in a vacuum…

Farmers may use APR for some assets and BPR for others - this means looking solely at the APR data and saying “well there were only X number who claimed for assets above Y” is potentially misleading. I haven’t been able to find a good answer that looks at both the APR and BPR claims in a unified way. And, I think that’s what is really needed to make a true “only X farms affected” type statement.

There’s also the fact that it appears Reeves and team didn’t even consult DEFRA until 24 hours before the budget announcement and that when this was brought up in the Houses of Parliament, the answers were much, much less reassuring than they should have been.8 Unfortunately, these shenanigans seem to be part and parcel of politics nowadays.

Conclusion

To be honest, when I started out on this journey I was largely on the farmer’s side - I felt like this was a continuation of a theme - stamping out traditional industries and selling them off to the benefit of bigger corporations. I then became increasingly skeptical that this was actually a more sinister campaign by rich land owners to trick the public by using (genuinely) struggling farmers as their mascots.

Now, after evaluating some of the debate and evidence in more detail, I believe the farmers do have a case and that the confusion around the affected numbers absolutely needs bottoming out before proceeding - in a way that both sides are happy with!

All that being said, regardless of any inaccuracies in the number of farms affected, I think the general point - that a huge percentage of the relief goes to the richest asset owners - will still stand. And, in a day and age where we hear of nurses and teachers going to food-banks, that’s just something I can’t get behind.

At the very least, with some better numbers, the threshold can either be (a) justified or (b) amended such that the effect on farmers is as targeted as the Government are claiming it will be. If that isn’t viable, then maybe a different way of identifying real family-farms should be used. After reflecting on the data, I think the threshold could lifted substantially and still achieve most of the key aims of the Government.

And finally, not that I’m shocked but … the most disappointing part of this (for me) was that there are so many people shouting at each other without even doing the bare minimum of research. Many of the pro-farmer supporters haven’t even done basic due diligence by reading the budget and government proposal; conversely, many of the pro-budget supporters have not even bothered to ask how a farm is run and operated.

As always, I hope people take the time to investigate the facts themselves before committing to more extreme measures and opinions. Alas, it seems everyone (myself included) wants to have an opinion without doing the requisite work to inform that opinion (especially if the facts contradict their opinion).

I'm a realist—I get that investigating issues takes time. But in an age of misinformation, where media prioritises engagement over accuracy, we should try to hold ourselves to a higher standard before enthusiastically spreading our conclusions to others.

Anyway, this article is getting far too long and I’ve just realised that I’ve only had two biscotti since 8am - I’m absolutely starving!

Until next time,

Pressy

https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/agriculture-in-the-united-kingdom-2023/chapter-14-the-food-chain#food-production-to-supply-ratio

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0305750X23002140

https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/balance-sheet-analysis-and-farming-performance-england/balance-sheet-analysis-and-farming-performance-england-202223-statistics-notice#return-on-capital-employed

https://ahdb.org.uk/trade-and-policy-total-farm-support-eroded-by-underspend-and-inflation

https://www.farmersguide.co.uk/rural/clarkson-speaks-out-about-alarming-suicide-rates-in-farming/

https://x.com/DanNeidle/status/1852064433738256394

https://www.gov.uk/hmrc-internal-manuals/inheritance-tax-manual/ihtm24150

https://x.com/nvonwestenholz/status/1857088039807312241